Like recipes or songs, crafts are the fingerprints of our histories. Some are the byproducts of traditional ways of life, like functional objects designed to be used daily, but also beautiful in their artistry. Others began their lives as purely decorative pieces, and over the years have evolved into something that holds far greater weight. All are celebrations of the vast scope of human creativity and ingenuity, preserved and shaped by artisans working to ensure their traditions thrive in an ever-changing world. It makes sense, then, that crafts are also a portal through which a traveler can experience a place—and its people—in a deeper way.

Of course, some parts of the world are already inextricably linked with their most famous crafts—we probably don’t need to introduce you to Moroccan rug weaving or Indian block printing. But a rising number of less exposed craft movements are landing on traveler’s radars, or in some cases, be rewarded with a long-awaited resurrection. In the collection of stories below, we spotlight five of them. Yulia Denisyuk travels to Okinawa to visit its bingata textile workshops—a quiet symbol of resilience in a Japanese prefecture that still bears the scars of war. Ashlea Halpern uncovers a similar legacy in Bosnia, but in the form of Konjic woodcarving, a UNESCO-recognized art form that has been passed down through generations, its artisans having never stopped sourcing materials from the same local forest. In Andalusia, Spain, the country’s rich equestrian culture still fuels its greatest craft: leatherwork, but which is now, as Nicola Chilton discovers, entering a new era in high fashion.

Down in the southern hemisphere, craftsmanship is providing new ways of looking at (or preserving) the present: Megan Spurrell discovers this in the Peruvian Andes, where meticulously handcrafted retablos depict museumworthy snapshots of daily life. And on the beaches of Lamu, Kenya, Sharon Machira posits that the new visual markers of the island’s identity can be found the ways in which contemporary designers are repurposing the sails of the island’s ancient dhow boats.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_2h3ckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_4h3ckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeRead on to learn more about these deeply rooted—yet sometimes lesser known—crafts hubs and how to experience them. And, of course, when you eventually visit them, make sure to bring an extra suitcase (or two) to schlep home all of the treasures you’ve picked up along the way. —Lale Arikoglu and Arati Menon

In Lamu, Kenya, Dhow Sails Are Fluttering With New Life

In the shipyards of Matondoni, a sleepy village in Lamu along Kenya’s northern Coast, the silhouette of a dhow taking shape is a common sight, its skeletal frame looming like ancient creature washed ashore. Here, hammers ping against nails, saws scrape along timber, and occasionally, a Bob Marley tune crackles to life from an old radio. The air is thick with sea salt and sawdust, and the sound of wooden frames creaking softly as builders move with the quiet patience of men who know you can’t rush a craft that has lived for centuries. This is where dhows are still made the Swahili way: slowly, by hand, by memory, and with a blessing from Allah…

Read more

In Peru’s Andes, the Centuries-Old Art of the Retablo Captures a Changing Country

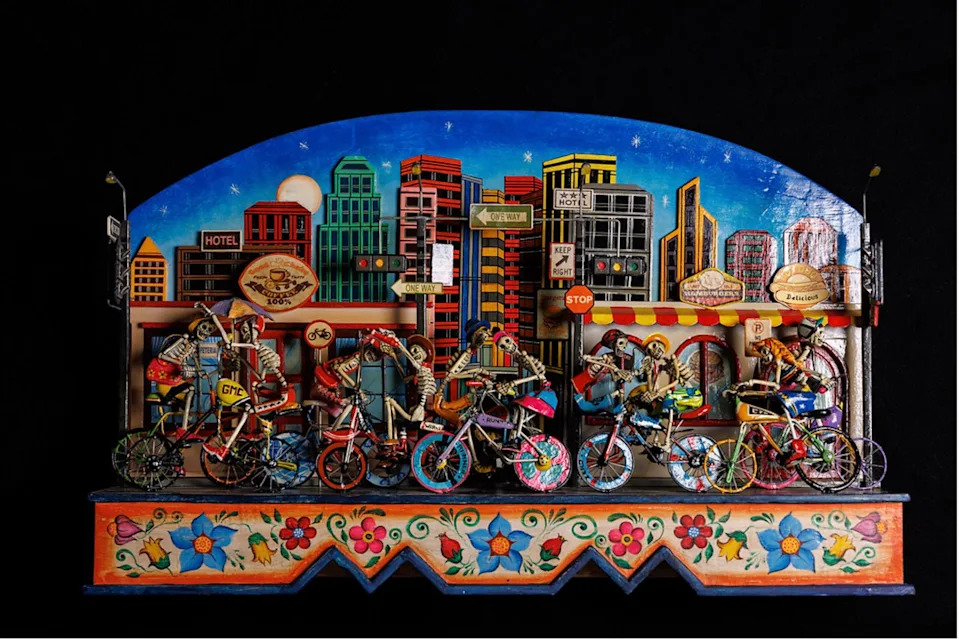

Picture the proportions of a shadow box: It could be the size of your hand, your head, or, in some cases, larger than your entire body. The exterior of this wooden box, often painted with vibrant floral flourishes, is deceptively simple. Pull open the two front doors and you’ll find an entire world within.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_2j3ckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_4j3ckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeIt might be a snapshot of daily life in the Andes—maybe a mercado, in which tiny figurines clamber over fruit and meat, or a celebration in which thousands of revelers dance in costume, their faces molded in exuberant joy, bitsy cans of Pilsen beer littering the ground. Some offer religious interpretations of the afterlife; others preserve moments in the country’s history. Traditionally, the figures that make up the interior of a retablo are made piece-by-piece, from a compound of ground stone, like alabaster or lime, mixed with binding agents like potato starch and cactus gum; and then even the finest details are painstakingly painted on by hand, traditionally with aniline dyes, for a process that can take many months or years to realize. Hour by hour, day by day, retableros—that is, retablos makers—breath life into the scenes they want to share…

Read more

Craft spotlight: Mahjong sets in Hong Kong

Mahjong, the beloved social strategy game that originated in Southern China in the 19th century, is played by millions worldwide. In cities across Asia, mahjong fans gather in the streets, parks, and parlors to this day. Nowadays, though, the craft that powered the game for centuries is getting harder to find. Most modern mahjong tile sets are machine-made, their designs stamped by plastic molds. Younger generations play the game on their devices, which has rendered the practice of making tiles—originally using materials like wood or ivory—by hand nearly obsolete. The craft, named an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong a decade ago, involves cutting and polishing the tiles then carving and coloring mahjong characters and symbols onto the surface. (One set of 144 tiles can take between eight to ten days to produce, costing up to 10 times more than the mass-produced machine replicas.)

In Hong Kong, a handful of artisans like Cheung Shun King are keeping the craft alive–for now. King is the third-generation owner and sole proprietor of Biu Kee Mahjong, one of the few remaining hand carved mahjong shops in the city. Located across from the famous Temple Street Night Market in the working-class Jordan neighborhood, his small space is where King spends most of his days, painstakingly carving traditional and custom designs for customers around the globe into each inch-long tile. Though he’s spent six decades in the business, King admits that he doesn’t know how to play. “On my one day off a year,” he says, “I don’t have time to play mahjong.” —Yulia Denisyuk

Inside the Leather Workshops of Andalusia

Javier Menacho’s atelier is a hive of quiet intensity. Upon walking in, I watch the leather artisan as he scores a perfect curve into a handbag panel with a compass. Soft piano music intermingles with the tweeting of sparrows outside, and my nose tingles with the heady scent of leather mixed with the musty perfume of incense burning on the windowsill. He's working on a clutch bag in bottle green leather, its surface embossed with geometric details inspired by Islamic art, gilded stars catching the light. The pattern, he tells me, draws upon the facade of La Giralda, the 12th century bell tower (and once a minaret) of Seville’s cathedral, as well as a tile from the ceramics neighborhood of Triana, and a floral Baroque motif. This is a man who clearly cares about details…

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_2lrckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_4lrckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeRead more

In Bosnia, a New Wave of Makers is Keeping the Art of Woodcarving Alive

Ping, ping. Tap, tap. Cling, cling. In historic Baščaršija, the Old Town of Sarajevo, I hear the metallic symphony before I see it.

I follow the sound through the cobbled alleys of Kazandžijska čaršija, the centuries-old Coppersmiths’ Quarter, where artisans have been shaping metal with mallets since the Ottoman Empire. Shiny objects spill from every storefront: pyramids of hand-hammered coffee pots glinting in the midday sun, disused mortar shells sprouting flower bouquets, trays of spent bullet casings fashioned into ballpoint pens. That remnants of a not-too-distant war are repurposed into kitschy souvenirs tracks with everything I’ve come to understand about Bosnia and Herzegovina—and its remarkably resilient people—over the past week. For every boot planted in a traumatic past, there are two eyes trained on a more hopeful future…

Read more

Craft spotlight: Glassblowing in the US

Glassblowing has long captured the American imagination—first brought over by British and German artisans, then steadily reshaped by geography, industry, and individual vision. The first documented effort to establish glassmaking in the Americas came in 1608, when the Virginia Company built a glasshouse at Jamestown (which you can still visit today). Though early efforts failed due to harsh conditions and economic instability, they laid the foundation for what would become a lasting American craft. In 1739, German colonist Caspar Wistar, backed by Quaker merchants in New Jersey, founded the first successful large-scale American glassworks, sparking a tradition that would evolve in distinctly local ways.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_2obckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_4obckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeThat evolution is especially vivid in the country’s unexpected hotbeds of glass artistry. In the Niagara region, a postwar studio glass boom thrived on the area’s industrial heritage and easy access to essential raw materials like sand, soda ash, and limestone. A three-hour drive south, Corning, New York is home to the world’s largest glass museum, where you watch master artisans at work. For more hands-on experiences, GlassRoots in Newark offers a dynamic calendar of classes and demonstrations.

On the West Coast, Seattle and Tacoma became glassblowing epicenters in the 1970s, with a distinctively experimental Pacific Northwest style that can be traced to Dale Chihuly, whose legacy lives on at the Pilchuck Glass School, founded in 1971. Meanwhile, urban centers like Pittsburgh and Asheville blend Appalachian and industrial aesthetics at studios such as the Pittsburgh Glass Center and the North Carolina Glass Center, where a new generation of artists is giving shape to American glass. —Christine Chitnis

In Okinawa, the Enduring Legacy of Bingata Textiles

At Chinen Bingata laboratory on the western edge of Naha in Japan's Okinawa prefecture, the 10th-generation bingata artist Toma Chinen is leaning over a piece of fabric that depicts hibiscus flowers on a yellow canvas. In the brightly lit, airy space, stacked rows of colorful textiles are stretched to dry along the walls. At a long, narrow table, a woman carves an ornate design of geese and peonies into a stencil, using a rectangle of dried tofu as a cutting board. Another paints a koi fish in a medley of purple, blue, and pink, dipping her short, stubby brush into red pigment mixed with soy milk. The artisans' slow movements look like a meditative dance. Chinen explains that the two-to-three-month process, which includes masking parts of the textile with a rice-based resist-dye paste, has barely changed since the time of the Ryukyu Kingdom, the trading nation with its own language, customs, and culture that flourished in Okinawa for 450 years beginning in the 15th century…

Read more

Credits

Lead editors: Lale Arikoglu, Arati Menon

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_2qrckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_4qrckr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeEditor: Erin Florio

Lead visuals: Pallavi Kumar

Supporting visuals: Charis Morgan

Social media: Emily Adler, Mercedes Bleth

Audience development: Abigail Malbon

Originally Appeared on Condé Nast Traveler

Trending Travel Destinations

Want to be the first to know? Sign up to our newsletters for travel inspiration and tips

A Guide to Korčula, Croatia, a Hidden Gem on the Dalmatian Coast

Why Everyone Will Be Going to Osaka in 2025

A London Local’s Melting-Pot Itinerary for Food, Drinks, and Chill Vibes in the Capital