Ptil Tekhelet Educational Center: Israel's newest, bluest cultural venue

“The main takeaway from The Tekhelet Educational Center is the deep appreciation for a beautiful mitzvah.”

You could say that Baruch Sterman has a case of the “blues.”

The doctor of physics, who worked as a hi-tech entrepreneur and technologist, founded Ptil Tekhelet – the Israel-based nonprofit Association for the Promotion and Distribution of Tekhelet – to help provide the blue dye described in the Torah for anybody who wants it. In 2012, he and wife, Judy, published The Rarest Blue. The book, which has sold more than 10,000 copies, details the search through centuries for the mysterious blue dye.

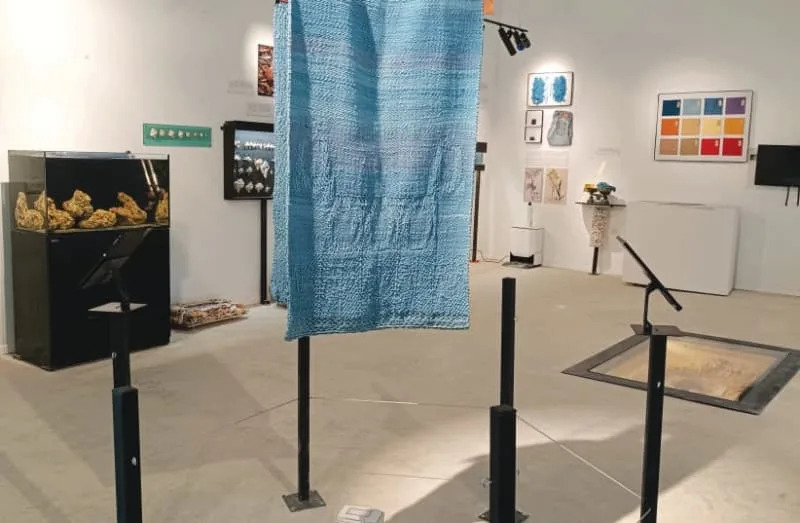

Sterman’s latest endeavor is the Tekhelet Educational Center in Kfar Adumim, near Jericho. The center features interactive exhibitions and activities, bringing the world of tekhelet to light through fascinating displays, videos, and active participation. At the center, visitors can explore the displays in the discovery room, enjoy multi-media presentations on the history and making of tekhelet, and actually experience the process of dying with it.

“The whole story of tekhelet brings together Jewish culture, history, archaeology, chemistry and, of course, Torah,” Sterman says.

“Discovering tekhelet and wearing it was not a possibility 40 or 45 years ago,” he says. “There was no tekhelet except for one small sect of Hassidim, the Radzyn, who thought their rebbe had discovered it. Tekhelet had disappeared 1,300 years ago in 650 CE.”

THE ROBE of the Kohen Gadol, made completely from tekhelet – beautiful and priceless; the garb of kings and emperors. (credit: Tekhelet.com)

THE ROBE of the Kohen Gadol, made completely from tekhelet – beautiful and priceless; the garb of kings and emperors. (credit: Tekhelet.com)People didn’t wear colored clothing in ancient times, the tekhelet expert explains. “The colors were mostly neutrals. Here and there, flowers and berries were used to color clothes – but even still, the dyes were earth tones.”

Sterman says the snail, discovered 4,000 years ago, brought a new dye and extremely vibrant blue or purple colors that didn’t fade. These colors – tekhelet (blue) and argaman (purple) – became a trend in the ancient Mediterranean fashion world. The dye was worth more than 20 times its weight in gold.

“Those who could afford it were called ‘the purple people,’” he says. “The traders were called porphyra, the Greek name of the murex snail, aka hilazon [in Hebrew], and also of the dye. It is also the core of the name Phoenicia, which means ‘the people who deal with purple.’”

The Phoenicians went all over the Mediterranean searching for snails and making a lot of money. In the Tanach, they are closely associated with tekhelet and argaman. Both the dye and the clothing were traded throughout the world – as far as Persia. When the Mediterranean was captured by the Romans, they took over the business. When Alexander the Great raided Cyrus’s tomb, he found items dyed purple and blue, Sterman says.

For Jews – more than a fashion trend

Roman emperors coveted the rich colors, and royalty became associated as being “born into the purple.” Purple and blue became associated with the royal house. That was the downfall of tekhelet, Sterman explains.

But for Jews, tekhelet was much more than a fashion statement.

“While Roman kings and princes all wore tekhelet, when the Torah says, ‘Put it on your clothes,’ it is reminding us that every single Jew is a king [because] he is a representative of the King of Kings,” Sterman says. “The Jewish religion is democratic, but it equalizes by elevating. Even the lowest people in society are elevated to the level of king and prince. The Jew has a mission: to save the world. When he looks at the tekhelet, he is being given a mission to remember all of the mitzvot and remember his personal responsibility and goal in life,” Sterman explains.

“When the Romans got their greedy little hands on the purple dying industry, it became much more expensive and harder to get,” Sterman continues. “They passed laws saying that having tekhelet in your home is a crime against the emperor. Romans and Jews developed a smuggling network for the dye, and it became very difficult to obtain. That is when more and more people began wearing white tzitzit. Only the most devout, richest Jews had the guts to wear tekhelet.”

The art of tekhelet was lost in the giant war of the 7th century between Byzantine Romans, Sasanian Persians, and the emerging Muslims, known as the Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628: the Last Great War of Antiquity. “During the Dark Ages, dye houses along the Mediterranean were destroyed, and all the knowledge of identification and tekhelet production became obsolete,” Sterman says.

While the Talmud, as well as Greek and Roman authors, wrote about tekhelet, it became very complicated to decipher what they wrote and understand exactly what the porphyra or the hilazon actually were. Two hundred years ago, archaeological and excavation finds were discovered. Scholars studied ancient languages, like Akkadian, and were learning more about chemistry, chipping away at the wall of obscurity of the ancient world.

At the beginning of the 1800s, there was a lot of archeology research being done throughout the Middle East, and the British and French began finding treasures of the ancient world. At the same time, the world was discovering synthetic dyes.

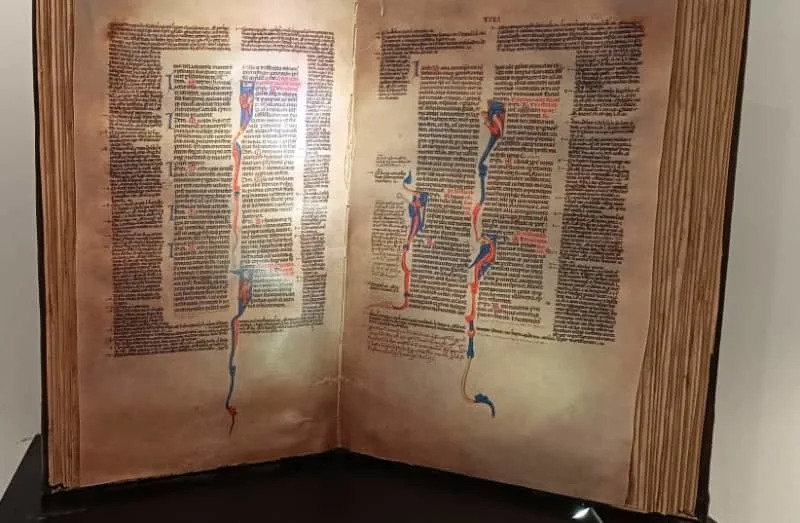

THE CODE of Justinian – a collection of laws developed under Byzantine emperor Justinian I. (credit: Tekhelet.com)

THE CODE of Justinian – a collection of laws developed under Byzantine emperor Justinian I. (credit: Tekhelet.com)The hunt for the snail

“This was not lost on the Jews,” Sterman says. “There were rabbis trying to find out what these ancient dyes were. Most notable among them was Rabbi Gershon Henoch Leiner from Radzyn [a town in eastern Poland]. His grandfather was the Ishbitzer Rebbe (the Mei Shiloah), who studied under the Kotzker Rebbe. Rabbi Gershon went to Italy, which had opened its first public aquarium in Naples in the 1800s, searching for the hilazon.”

Secular scientists were also studying snails, honing in on specific sea snails in the murex family, says the Ptil Tekhelet founder. “They knew these snails could make dyes. Chemists were analyzing them, and they were finding piles of ancient snail shells in Tyre, Turkey, Cyprus, Greece, Morocco, Tunisia/Carthage, and Italy.”

But what did these large piles of snail shells mean?

Sterman explains, “A few piles of shells probably indicated it was somebody’s supper. But a lot of snails? That’s a production facility.”

As scientists began experimenting with the dye, they were able to make the purple argaman color.

The problem is that the chemists were only able to obtain a purple dye from the murex snails; but according to the Torah, tekhelet is supposed to remind us of the sea or the sky – so it was blue, not purple.

Rabbi Yitzhak Halevi Herzog, the first chief rabbi of the State of Israel and grandfather of President Isaac Herzog, wrote a doctorate in 1914 on tekhelet at the University of London. Besides speaking 12 languages, the distinguished scholar coined the phrase “Hebrew porphyrology,” based on the above-mentioned Greek name of the murex/hilazon snail.

Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to get past the purple; the trail went cold.

Discovered by accident

In 1985, Prof. Otto Elsner working at Shenkar College of Fibers in Herzliya made an accidental discovery. He was researching properties of the dyes that came out of the snail and noticed that at very specific times in the dying process, if you expose the dye to sunlight, it turns blue, not purple.

Although Elsner wasn’t interested in tekhelet, his research was picked up by Rabbi Eliyahu Tavger, who began the process of making the ritual blue dye. While looking for scuba divers to help him find the mysterious snails, he met Sterman and dentist Ari Greenspan. The two went diving off the northern coast of Israel and found plenty of murex snails. As it turns out, the snails abound all over the Mediterranean.

Sterman joined with Tavger and formed the Ptil Tekhelet nonprofit organization.

With catering options and a large picnic area that can accommodate up to 100 guests, the Tekhelet Educational Center in Kfar Adumim is not only educational but has become an ideal place to celebrate bar mitzvah and hanahat tefillin ceremonies, where a 13-year-old boy comes of age and puts on tefillin for the first time.

“We had such an amazing, meaningful experience at Ptil Tekhelet today!” one patron wrote enthusiastically after celebrating his son’s tefillin-laying ceremony. “The guide was so knowledgeable, and his passion really came through. The icing on the cake was the [tekhelet-making] demo at the end. The entire group was in absolute amazement, seeing the process happen. I think this place is a must-visit for every religious boy.”

Sterman concludes, “The main takeaway from The Tekhelet Educational Center is the deep appreciation for a beautiful mitzvah.”