2,000 ‘plastivore’ caterpillars can gobble a stubborn plastic bag in 24 hours

A new study explores the potential of caterpillars to degrade polyethylene plastic, the most common type of plastic globally.

A team at Brandon University in Canada, headed by Dr. Bryan Cassone, researched waxworms, the caterpillars of the greater wax moth (Galleria mellonella).

Surprisingly, just 2,000 waxworms can break down an entire polyethylene bag in as little as 24 hours. That's a dramatic difference from the hundreds of years it usually takes.

“Around 2,000 waxworms can break down an entire polyethylene bag in as little as 24 hours, although we believe that co-supplementation with feeding stimulants like sugars can reduce the number of worms considerably,” said Cassone, a Professor of Insect Pest and Vector Biology in the Department of Biology at the university.

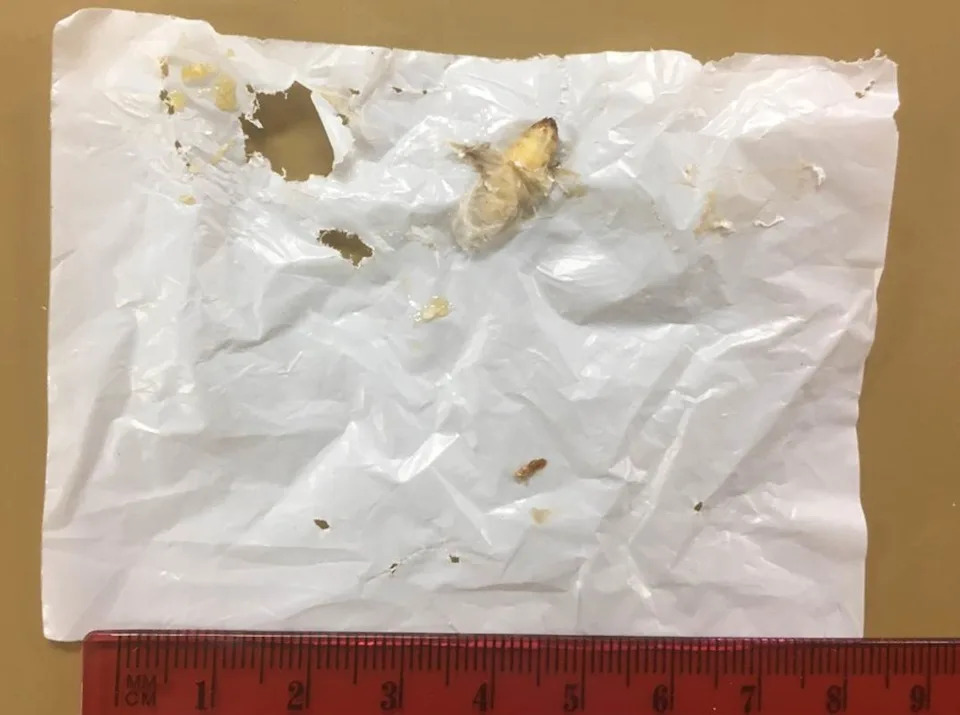

Waxworm eating plastic. Credit: Harald Grove via email.

Waxworm eating plastic. Credit: Harald Grove via email.Munching on plastic waste

Polyethylene is the most widely produced plastic globally, with over 100 million tonnes manufactured annually for a vast array of products, from grocery bags to various forms of packaging.

However, it poses a major environmental challenge due to its chemical toughness and resistance to decomposition.

Full degradation of this material can stretch over decades or even hundreds of years.

In 2017, a discovery revealed that these little creatures can eat polyethylene.

New research shows that “plastivore caterpillars” can break down plastics in just days, converting them into body fat.

Dr. Cassone's team, using diverse scientific methods, studied the interaction between waxworms and their gut bacteria to understand plastic degradation.

The research shows that waxworms metabolize ingested plastics into lipids stored as body fat.

“This is similar to us eating steak – if we consume too much saturated and unsaturated fat, it becomes stored in adipose tissue as lipid reserves, rather than being used as energy,” explained Cassone.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e5EEAH773uw&pp=0gcJCcEJAYcqIYzv

Impact of an all-plastic diet

Apart from the biological processes involved, the team assessed the health impact of an all-plastic diet on the worms.

So here’s a catch. While waxworms easily munch on plastic, an all-plastic diet is a death sentence.

The plastivore caterpillars don't survive over a few days and even experience mass loss.

However, Cassone is optimistic. He believes they can create a "co-supplementation" – basically, adding other food – that not only restores their health but makes them thrive.

This research points to two exciting possibilities for tackling plastic pollution.

“Firstly, we could mass rear waxworms on a co-supplemented polyethylene diet as part of a circular economy,” he said.

Alternatively, researchers could work on replicating the plastic breakdown process in a lab setting, without the need for the animals themselves. This means identifying the exact biological mechanisms and enzymes responsible and then potentially using them in industrial processes without the worms themselves.

And there's a bonus! Large-scale waxworm farming is expected to produce a huge amount of insect biomass. Preliminary data suggests this could be a highly nutritious food source for commercial fish farming.

Even if waxworms could effectively degrade plastic, dealing with the 100 million tonnes of polyethylene produced annually would require billions of caterpillars eating continuously.

A critical, often overlooked issue with mass-rearing waxworms is their natural diet: they feed on beeswax, posing a significant threat to bee colonies worldwide. It could be devastated by an explosion in wax moth populations.

Lots of past studies have explored the potential of plastic-eating fungi and bacteria for bioremediation, but a major hurdle remains: their adaptation and efficient deployment at scale.

Therefore, the question remains: Could these tiny "plastivore" caterpillars be a key player in a cleaner, more sustainable future?

The findings were presented at the Society for Experimental Biology Annual Conference in Antwerp, Belgium, on July 8, 2025.